Blame it on the age of Zoom, but before our much-anticipated interview begins, there’s a customary exchange of comments on each other’s backdrops. Not that there’s any competition. Dr Laszlo’s is far superior and he talks me through the bespoke piece of Chinese art behind him. It’s a majestic ink drawing of mountainous horizons with a element of calligraphy added. “Peace” is apparently what it says – in which case, there’s a sense of pictures merging with words here and perhaps a foreshadowing of the upcoming conversation.

Born in 1932, Dr Laszlo grew up in a Hungary that was reeling from the inter-war period and witnessing the rise of fascism at home and abroad. Aided by an early talent for music, Laszlo left shortly after the post-war Stalinisation of the country. With a life in Western Europe ahead of him, he graduated from the Sorbonne in Paris and moved into the world of philosophy. The rest, as they say, is history.

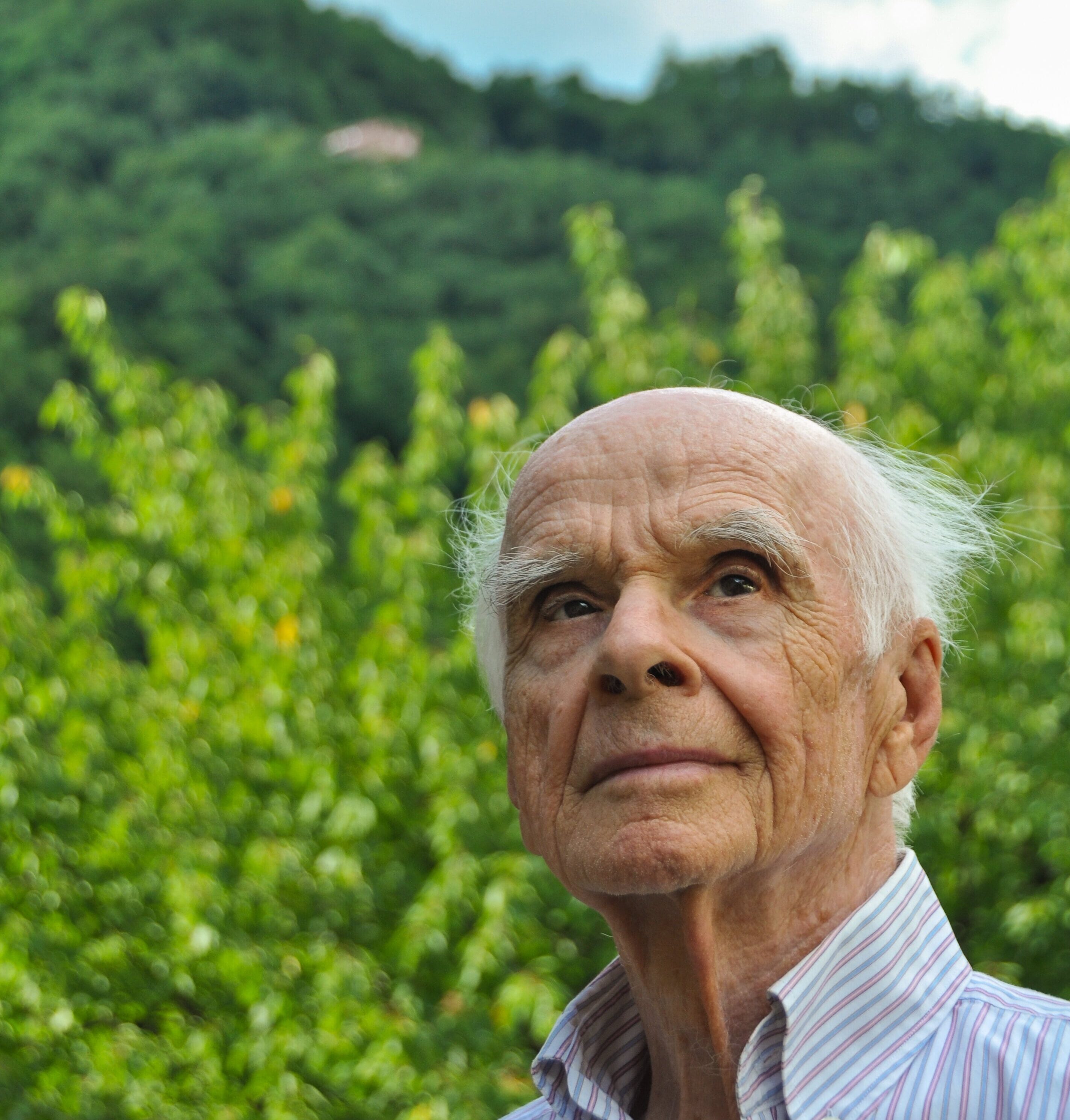

In this first of two parts, Global Man‘s Yassin El-Moudden sat down in conversation with the thought-provoking philosopher of science, as he opened up on his early life, his influences and the concept of freedom.

Q: This is the cliched beginning of an interview, where I’d normally introduce you, but actually how would you introduce yourself, Professor?

A: : I’m a seeker. I’m out to look for things, to try to make sense of things. That’s my mission and I try to communicate to others, if I come across something that I’m convinced of. If it seems plausible to me – no absolute certainty – but if these things can be more or less likely to be true, then how can that be used as a way to establish a higher level of wellbeing, which we certainly need.

Q: Indeed. We live now in a time with a lot of historical comparisons thrown about, including by many people half your age! Let’s bookend this moment, starting from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to – from a Eurocentric perspective – the crisis in Ukraine. Looking back on your life, how do you see this particular moment we’re going through?

A: It’s part of a process of change and transformation. These processes are never smooth, never linear. They’re always leaping, going through points of chaos and breakdowns until there is a breakthrough. If there isn’t a breakthrough, then, of course, that particular species or society disappears. Yet, we have within us a consciousness which enables us to perceive how to proceed – and to proceed purposefully – if only we would act according to our insight, which we don’t always do.

Change is happening now. This change could spell the end of civilisation – possibly even the end of this species to which we belong – but change is not only change. It is also, and above all, about opportunity. So this process is a trial – a trial by fire as it were – for our resistance, for our wisdom, to pull ourselves forward. To shift, in the terms I’m now using, upwards, instead of allowing ourselves to be pull down into greater and deeper crisis.

So, we are in a process of evolution, of rapid evolution and change. The opportunity is given to us to evolve to higher levels. It’s up to us and the wisdom of people today – the good common sense of people – to make use of this tremendous period of challenge, of trial and to make use of it so we move forwards, not backwards.

Q: You’ve mentioned change and chaos a couple of times, Professor. I take it you went into exile at quite a young age?

A: Well, we went out through the Iron Curtain, which meant that we could only have one suitcase each. No more than what we could carry. I remember we had some foreign currency that we managed to get together. It was sewn into the soles of our shoes, so that somehow we would have something to live on.

When we left, it was actually to go to Geneva, to an international music competition. I couldn’t enter the previous year as I was 14, so I had to wait until I could enter at 15. I was fortunate enough to win one of two grand prizes, which led to concert invitations in France and finally my debut recital in New York.

Q: Some have said that a new Iron Curtain is descending over Europe. Now you lived behind the actual Iron Curtain of the 20th Century…

A: Yes, but I was very young! I left as a teenager but sure enough, there was a dictatorship imposed by the Soviet Union, although the communist regime was always kind to artists. They were proud of artists and offered many privileges to artists and writers – as long as they don’t criticise the system! They wanted to use artists, of course, as propaganda for themselves.

As a young pianist, I wasn’t in a place to be a problem for the government. So, I didn’t particularly suffer except that our family suffered. My grandfather and father had founded a small shoe factory that operated along very democratic principles. For example, they only employed unionised workers. Nevertheless, the regime nationalised it and even forbade my father from taking employment in what used to be his own factory. Then, he had to follow us and emigrate.

Q: It’s incredible to think that music was something that offered actual refuge for you. During times of difficulties, some people find emotional refuge in music. Of the classical repertoire, who are your favourite composers?

A: As the years go by, I look more and more for music that seems simple and harmonious. The music of Mozart, of Bach, of Schubert. Amongst the modernists, there is Bartók. A seemingly dissonant kind of music, which has a very basic message and a basic logic of its own, which is very strong. It grasps you at the seat of your soul, as it were.

I’m looking for music that is simple, makes sense, coherent with one thing leading to another. Not just sounds put together but something that is being said, something communicated, be it an attitude or sense of feeling, a love, an appreciation, a friendship. It’s just a form of relaxation, together with others or with nature. This is the music that I like.

Q: I want to delve into your philosophical background. How did you start off your journey and what were you main influences?

A: That’s a big question. I’ve devoted two books to trying to make sense of my journey. So, it’s difficult to summarise in a few words.

I have always been curious and interested and not ready to accept things, ideas and behaviours just because they were given and dominant around. I always wanted to find out what is really case, how we can know it and how we can act in a better way. These were the key elements that drove me from one stage to another.

I was fortunate to have been born into a family in Budapest where my mother was an aspiring pianist, my uncle was a philosopher, there was a lot of music and discussion in our house. I think that left its mark on my further development. First, as a musician and then in my late teens and 20s when I changed to another profession, the academic world. From the academic world, I moved forward to the club of Rome, the club of Budapest and the United Nations Institute for Teaching and Research. In the 1970s, I moved into what I might call an “activist phase”. That is, understanding but using that understanding to create a better world.

Q: Am I correct in understanding that you subscribe to a form of philosophical idealism?

A: Well, I would agree. In a sense, Platonism, I would agree to. I believe that there is a higher level of consciousness, mind and will in the world. You can call it this or that – a Messiah, or God, or whatever. It’s in the universe, there is a drive forward. The world is not a passive slate where we can inscribe what we want. The world is a very active, moving, dynamically evolving sphere in which we are an element, whether we know it or not. If we don’t know it and we exceed it, then we do it at our own peril.

The conversation continues in its second and final part.

For readers based in the UK, there will be an opportunity to meet Dr Ervin Laszlo in person on Thursday 14th July at the Global Woman London Club. Click here to book your ticket.